Cultural Practices

The Law on Advancement of Culture is based on the cultural dynamics that are found in the community every day, from the most traditional culture to the most contemporary one, from the one that is on the brink of extinction to the one that continues to develop.

It talks about how we assimilate foreign cultures, process them into a new culture, and continue to develop them.

How we can continue to contribute to the world’s culture.

All cultural practices and products are a mix and combination of a community with different cultures.

We don’t need to be afraid of foreign cultures. We can actually continue to contribute to the world.

One element of culture can contain more than one value or meaning.

Culture advancement means developing every element in the cultural ecosystem and other different ecosystems.

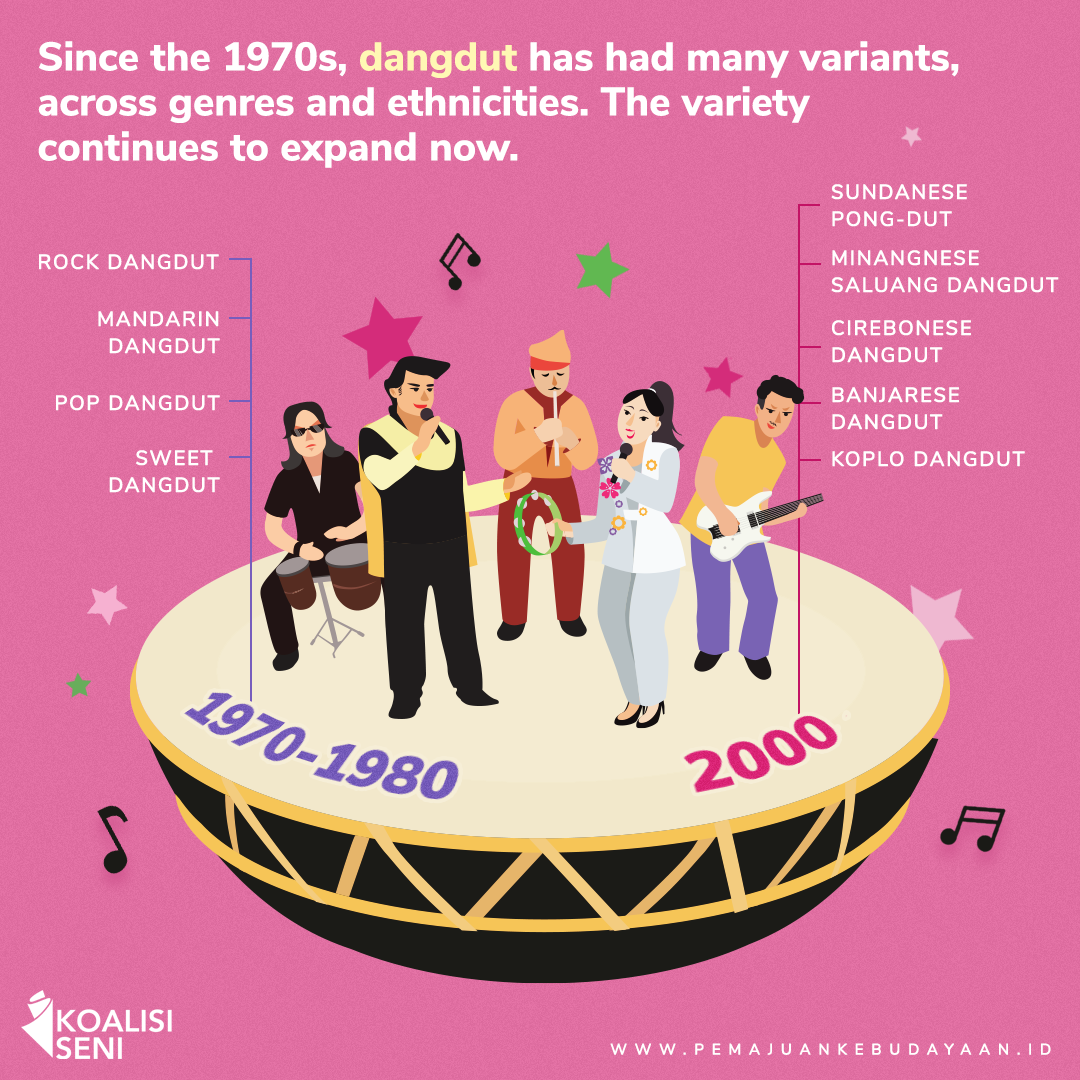

Our civilization grows and develops because people from various ethnicities and regions meet with each other. Dangdut, for example, was created from a series of intercultural interactions in the archipelago, both intentional and unintentional. The distinctive sound of dangdut is a blend of the Malay Orchestra, which was popular in Indonesia in the 1930s to 1950s, and the music in Indian movies, which dominated viewing in Indonesia during the Sukarno era due to the ban on imports of European and American films. Dangdut, which continues to evolve over time, currently has new variants such as rock dangdut and regional dangdut.

Another example: keroncong. Now recognized as part of the archipelago’s musical repertoire, keroncong was originally the result of a long journey that began in Africa. Trade and slavery brought a number of West and North Africans—and their musical traditions—to Portugal since the 7th century. There, they performed dance music for the nobility and the royal family, who later sponsored a number of expeditions to the east in the name of profit, religion, and national propaganda in the 15th century. This imported culture was brought to India, Malacca, the Nusa Tenggara Islands, to Batavia. In every stopover, keroncong was enriched to become the music we know today.

Our cultural wealth enriches the world’s culture. Camphor, for example, was once a preservative for the mummies of kings in Egypt. A network of Arab, Indian, and Chinese traders brought it from the port of Barus in North Sumatra to the tip of Africa. We can see similar developments in silat. Prominent in the archipelago for a long time, silat has only become global as popular culture since the popularity of The Raid in 2011. After that, the three main actors of the Gareth Evans-directed film—Iko Uwais, Yayan Ruhian, and Joe Taslim—are selling well as actors and choreographers of Hollywood action movies.

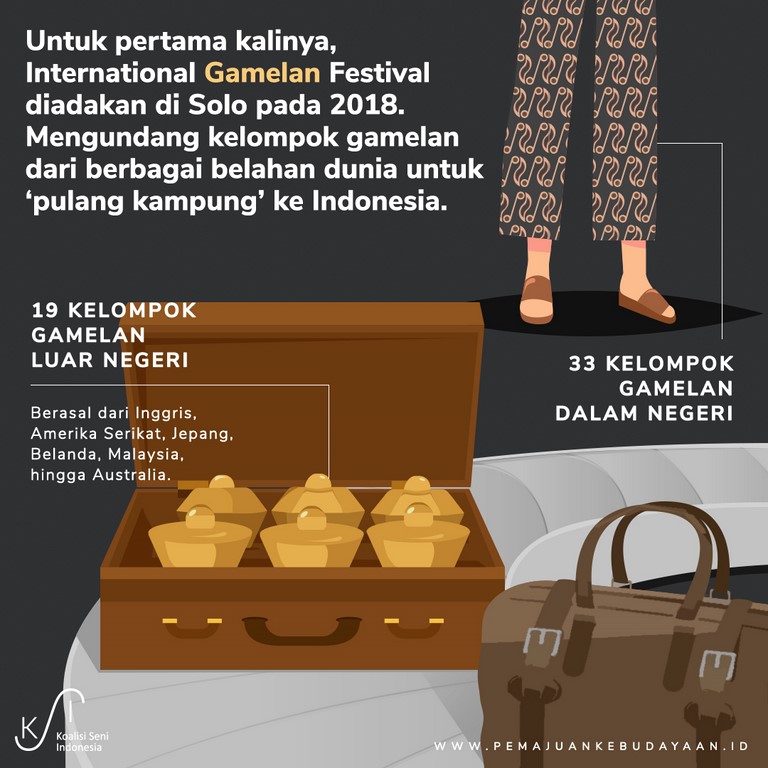

The challenge now is how we can play an active role in developing the archipelagic culture in the world’s social circle. Oftentimes, it is foreigners who are more interested in our culture than our people. Gamelan, for example, is widely adopted in world music treasures. Its distinctive sound invites the experimentation of many world musicians, from youth icons such as Bjork and Sonic Youth to well-known composers such as Philip Glass and Ryuichi Sakamoto.

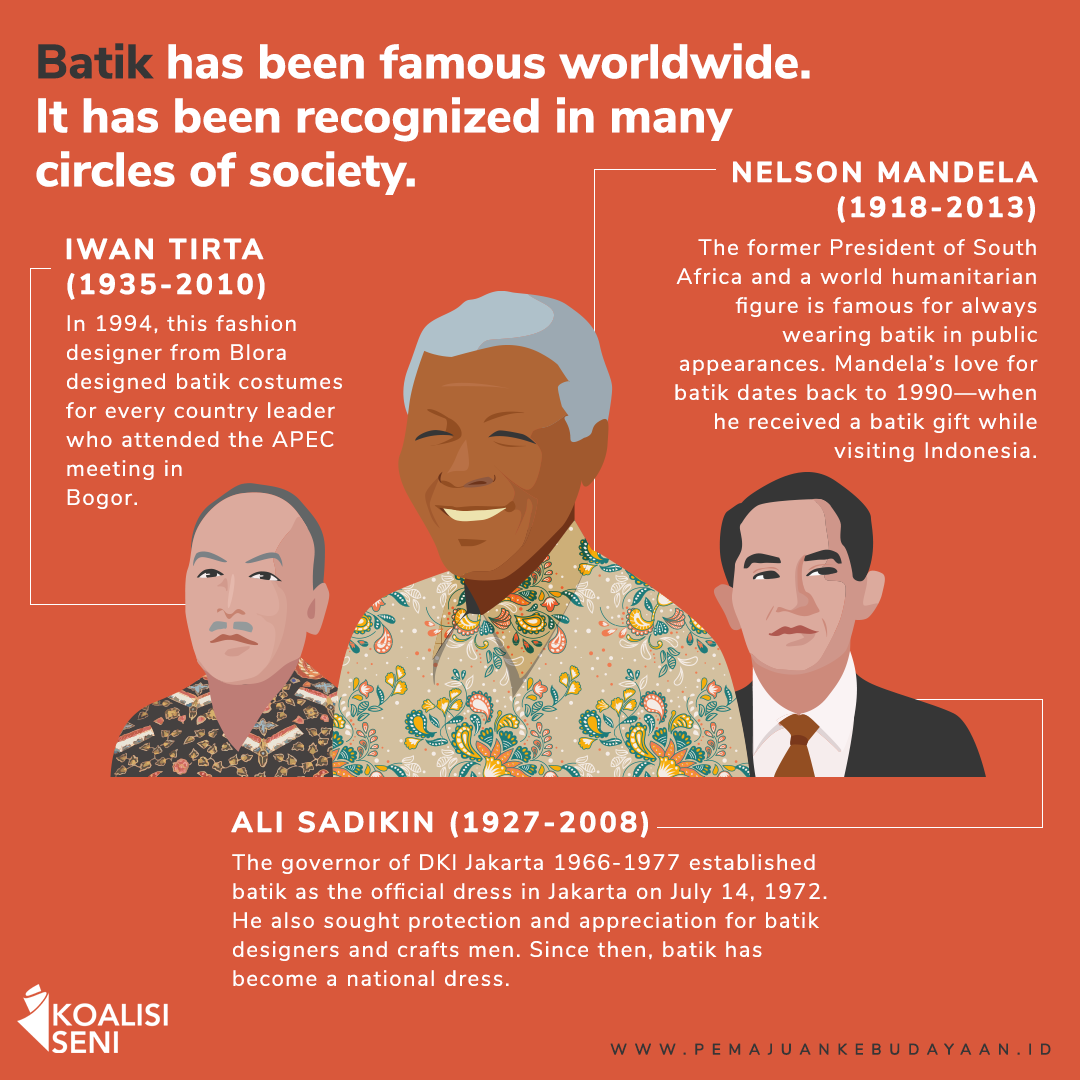

Batik experienced a similar fate. Its unique motifs make batik so popular that it appears in various circles of the world, from fashion shop windows to international meeting forums. One of the actors is Nelson Mandela, a humanitarian figure and former president of South Africa who is known to always wear batik in his public appearances.

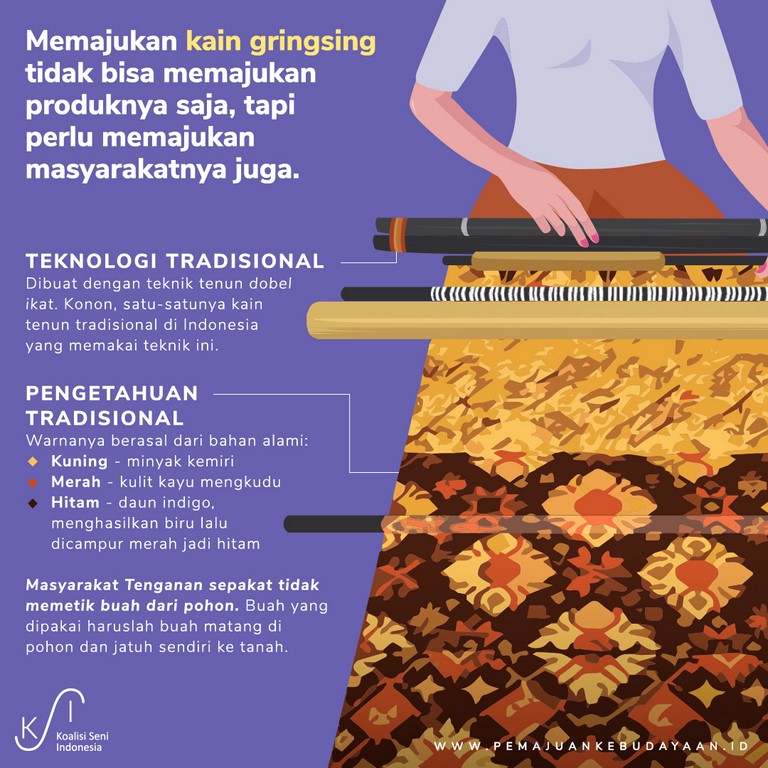

Culture exists as a fulfillment of human needs. With such a variety of human needs, of course, an element of culture can be interpreted as more than one value—depending on who interprets it. Gringsing fabric, for example, generally may be more meaningful as a souvenir for travelers. However, for the people of Tenganan village in Bali, Gringsing is a requirement for public participation. Without wearing it, a Tenganan resident cannot participate in village meetings in the traditional hall. Gringsing fabric is also interpreted by Tenganan residents as a repellent to any bad fate—it is often worn in tooth-cutting rituals. The name Gringsing means “not sick.”

The Law on Advancement of Culture is sensitive to the flexibility of society in culture. Therefore, the Law on Advancement of Culture can classify a cultural product into more than one type of the Object for Cultural Advancement. Based on the use of society, Gringsing fabric is part of the customs and rituals. Based on the physical form, it is part of art because of the artistic value of the motif design. Based on the production process, it is part of traditional technology and traditional knowledge, because of the specific manufacturing techniques in the Tenganan village environment and the collection of raw materials based on the wisdom of the local community.

Cultural problems cannot be solved only by fixing one aspect. Thus, in fixing problems in the world of cinema, for example, there are many aspects that need to be addressed besides the number of cinemas. The film ecosystem covers many aspects, from production, distribution, screening, appreciation, education, to archiving—every aspect has its own needs that must be researched and addressed. Pre-COVID 19 pandemic, the amount of production was getting higher, but the distribution channels were not adequate. Every year we produced 2,000 titles, but the cinema network could only accommodate 400–500 films, sharing with imported movies. It needs a great circulation system to accommodate the diversity of movies.

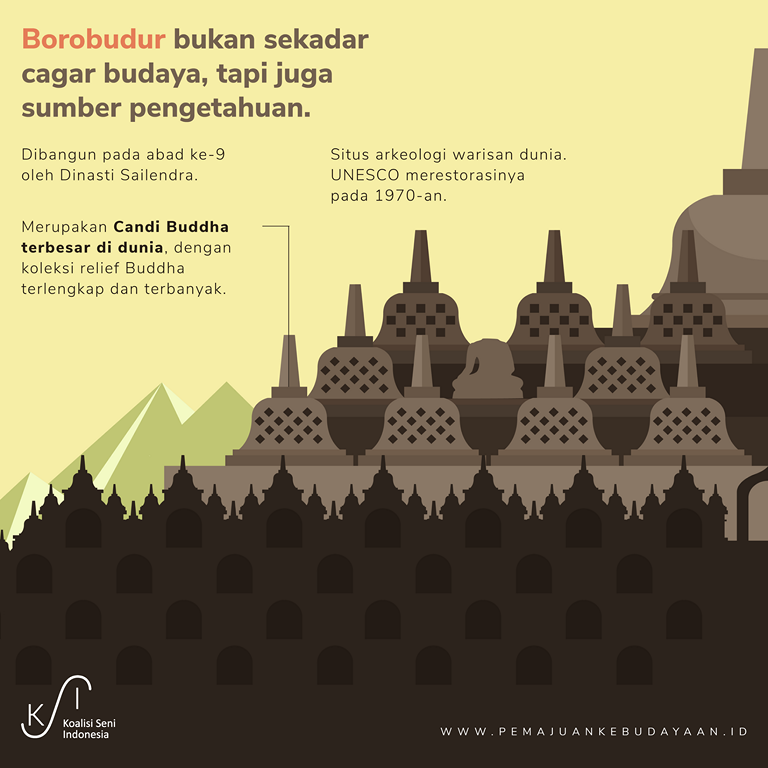

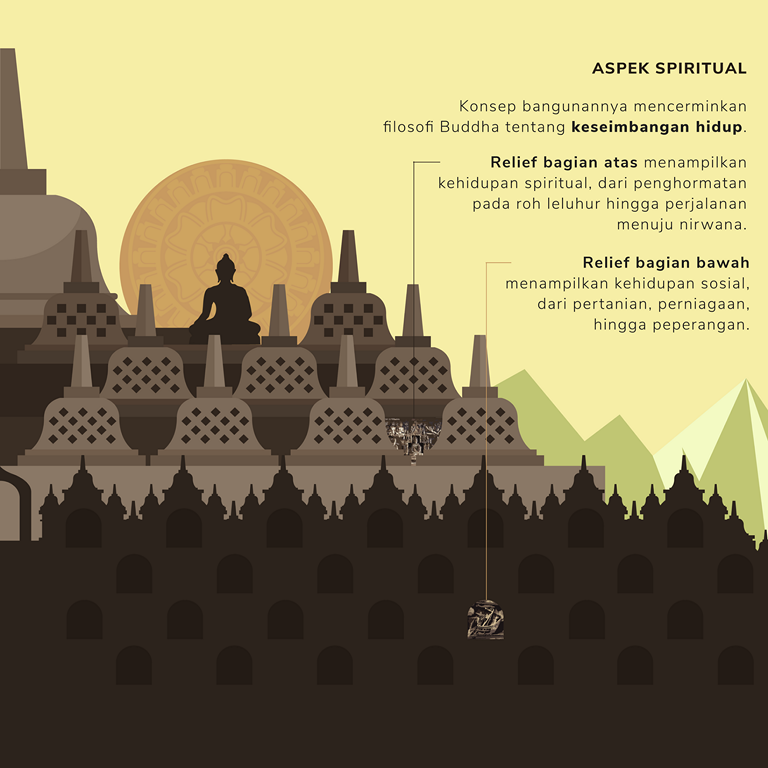

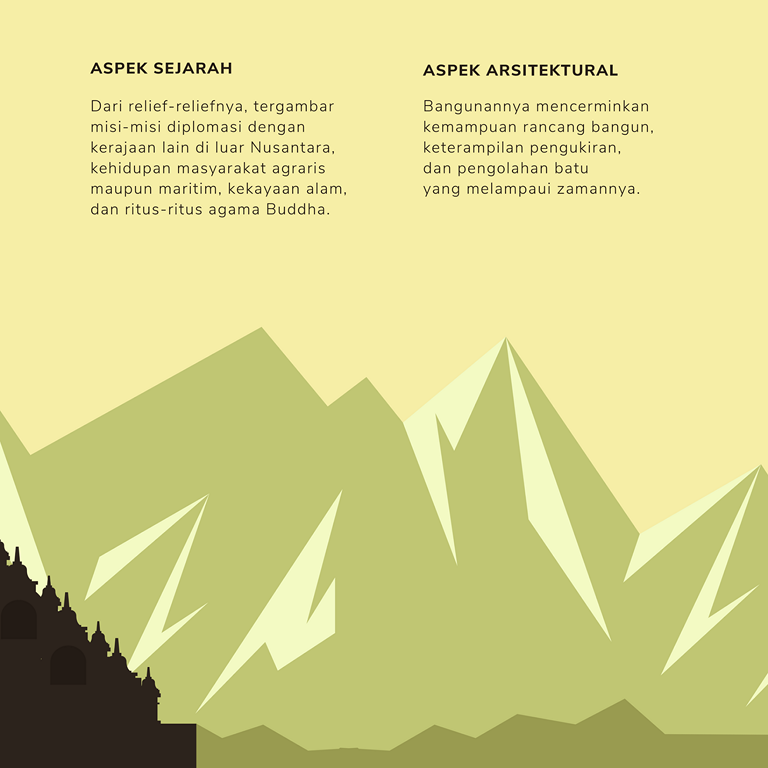

On the other hand, every cultural product has a value that goes beyond the visible. Borobudur, for example, is not only a cultural heritage but also a source of knowledge. The concept of the building reflects the Buddhist philosophy of life balance. Its design contains architectural insights that transcended its time. There are many things that can be processed from knowledge rather than just a matter of preserving cultural heritage. In every culture, there are many elements that need to be considered, and there are many aspects of the ecosystem that need to be brought together.

All cultural practices and products are a mix and combination of a community with different cultures.

Our civilization grows and develops because people from various ethnicities and regions meet with each other. Dangdut, for example, was created from a series of intercultural interactions in the archipelago, both intentional and unintentional. The distinctive sound of dangdut is a blend of the Malay Orchestra, which was popular in Indonesia in the 1930s to 1950s, and the music in Indian movies, which dominated viewing in Indonesia during the Sukarno era due to the ban on imports of European and American films. Dangdut, which continues to evolve over time, currently has new variants such as rock dangdut and regional dangdut.

Another example: keroncong. Now recognized as part of the archipelago’s musical repertoire, keroncong was originally the result of a long journey that began in Africa. Trade and slavery brought a number of West and North Africans—and their musical traditions—to Portugal since the 7th century. There, they performed dance music for the nobility and the royal family, who later sponsored a number of expeditions to the east in the name of profit, religion, and national propaganda in the 15th century. This imported culture was brought to India, Malacca, the Nusa Tenggara Islands, to Batavia. In every stopover, keroncong was enriched to become the music we know today.

We don’t need to be afraid of foreign cultures. We can actually continue to contribute to the world.

Our cultural wealth enriches the world’s culture. Camphor, for example, was once a preservative for the mummies of kings in Egypt. A network of Arab, Indian, and Chinese traders brought it from the port of Barus in North Sumatra to the tip of Africa. We can see similar developments in silat. Prominent in the archipelago for a long time, silat has only become global as popular culture since the popularity of The Raid in 2011. After that, the three main actors of the Gareth Evans-directed film—Iko Uwais, Yayan Ruhian, and Joe Taslim—are selling well as actors and choreographers of Hollywood action movies.

The challenge now is how we can play an active role in developing the archipelagic culture in the world’s social circle. Oftentimes, it is foreigners who are more interested in our culture than our people. Gamelan, for example, is widely adopted in world music treasures. Its distinctive sound invites the experimentation of many world musicians, from youth icons such as Bjork and Sonic Youth to well-known composers such as Philip Glass and Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Batik experienced a similar fate. Its unique motifs make batik so popular that it appears in various circles of the world, from fashion shop windows to international meeting forums. One of the actors is Nelson Mandela, a humanitarian figure and former president of South Africa who is known to always wear batik in his public appearances.

One element of culture can contain more than one value or meaning.

Culture exists as a fulfillment of human needs. With such a variety of human needs, of course, an element of culture can be interpreted as more than one value—depending on who interprets it. Gringsing fabric, for example, generally may be more meaningful as a souvenir for travelers. However, for the people of Tenganan village in Bali, Gringsing is a requirement for public participation. Without wearing it, a Tenganan resident cannot participate in village meetings in the traditional hall. Gringsing fabric is also interpreted by Tenganan residents as a repellent to any bad fate—it is often worn in tooth-cutting rituals. The name Gringsing means “not sick.”

The Law on Advancement of Culture is sensitive to the flexibility of society in culture. Therefore, the Law on Advancement of Culture can classify a cultural product into more than one type of the Object for Cultural Advancement. Based on the use of society, Gringsing fabric is part of the customs and rituals. Based on the physical form, it is part of art because of the artistic value of the motif design. Based on the production process, it is part of traditional technology and traditional knowledge, because of the specific manufacturing techniques in the Tenganan village environment and the collection of raw materials based on the wisdom of the local community.

Culture advancement means developing every element in the cultural ecosystem and other different ecosystems.

Cultural problems cannot be solved only by fixing one aspect. Thus, in fixing problems in the world of cinema, for example, there are many aspects that need to be addressed besides the number of cinemas. The film ecosystem covers many aspects, from production, distribution, screening, appreciation, education, to archiving—every aspect has its own needs that must be researched and addressed. Pre-COVID 19 pandemic, the amount of production was getting higher, but the distribution channels were not adequate. Every year we produced 2,000 titles, but the cinema network could only accommodate 400–500 films, sharing with imported movies. It needs a great circulation system to accommodate the diversity of movies.

On the other hand, every cultural product has a value that goes beyond the visible. Borobudur, for example, is not only a cultural heritage but also a source of knowledge. The concept of the building reflects the Buddhist philosophy of life balance. Its design contains architectural insights that transcended its time. There are many things that can be processed from knowledge rather than just a matter of preserving cultural heritage. In every culture, there are many elements that need to be considered, and there are many aspects of the ecosystem that need to be brought together.